Tavern Owners harrassed by police. Business is being severely impacted because local police walk dogs through the tavern. They return every night Friday and Saturday and basically camp out, moving from one tavern to another. Business is seriously being impeded. Even law abiding citizens who just simply feel intimidated by large cops with mean dogs refuse to come in. Any ideas?

See Benigni v City of Hemet, 9th Circuit case.

From Forensic Magazine, a short article on studies on dog sniffs. Note the mention of the “Rosenthal effect”, the subconscious cues the handler can give the scent dog. (Essentially the same problem one encounters with confirmation bias and non-blind tests.) http://www.forensicmag.com/articles.asp?pid=86

Drug dog alert cannot be used to get warrant for a home? More leashes for drug dogs. The police may not use a drug dog alert outside the defendant's home to obtain probable cause for a warrant to search the home, the Fourth DCA ruled February 15, 2006. State v. Rabb, ___ So. 2d ___, 31 F.L.W. D510 (4th DCA 2/15/2006). The case can be viewed at http://www.4dca.org/Feb2006/02-15-06/4D02-5139.op.pdf or under the "opinions" section at http://www.4dca.org and then looking under the 2/15/06 opinion date, or try an internet search for the case name. When the government should chase robbers, the government chases Rabb (for pot). The government robbed Rabb of his pot? The lengthy decision, extensively discussing the use of non-traditional methods of obtaining evidence for warrants, was issued upon remand from the U.S. Supreme Court in Florida v. Rabb, 125 S. Ct. 2246 (2005). On May 16, 2005, The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) in case # 04-914 had granted a petition for a writ of certiorari the earlier Rabb appeals judgment was vacated and the case was remanded to the District Court of Appeal of Florida, Fourth District, for further consideration in light of Illinois v. Caballes (2005). The police got an anonymous tip that defendant was growing marijuana in his home. They made a traffic stop of defendant and found marijuana, and they then took a drug dog to his home. The dog alerted on the residence, and the officers stated that they could smell marijuana at the front door. They obtained a warrant, and the search revealed growing marijuana. "Given the shroud of protection wrapped around a house by the Fourth Amendment, we conclude that Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27 (2001), controls the outcome of the case at bar. In Kyllo, law enforcement, believing Kyllo to be growing marijuana in his house, employed an Agema Thermovision 210 thermal imager to scan his house and reveal heat signatures. Id. at 29. The thermal scan revealed that a portion of the roof and one wall of the house were relatively hot compared to the remainder of the house and surrounding houses. Id. at 30. As a result, law enforcement concluded that Kyllo was employing halide lamps to grow marijuana. Id. Combined with further information gathered, law enforcement obtained a warrant and discovered in excess of one hundred marijuana plants in Kyllo's house. Id. Kyllo was charged with manufacturing marijuana and moved to suppress the marijuana evidence seized from his house based on the use of the thermal imager. Id. The trial court and appellate court determined that use of the thermal imager did not amount to a search of Kyllo's house. Id. at 30-31. "The United States Supreme Court reversed the lower courts, holding: "We think that obtaining by sense-enhancing technology any information regarding the interior of the home that could not otherwise have been obtained without physical "intrusion into a constitutionally protected area," constitutes a search -- at least where (as here) the technology in question is not in general public use. Id. at 34. The Court also noted: "The Government maintains, however, that the thermal imaging must be upheld because it detected 'only heat radiating from the external surface of the house.' . . . We rejected such a mechanical interpretation of the Fourth Amendment in Katz, [another vice case -gambling case- see the bottom of this page] where the eavesdropping device picked up only sound waves that reached the exterior of the phone booth. Reversing that approach would leave the homeowner at the mercy of advancing technology -- including imaging technology that could discern all human activity in the home. While the technology used in the present case was relatively crude, the rule we adopt must take account of more sophisticated systems that are already in use or in development. 533 U.S. at 35-36. ... We now turn to the intersection between the staunchly-protected house, as discussed in Kyllo, and law enforcement's use of dog sniffs by trained canines to detect contraband. It is true that the United States Supreme Court held in United States v. Place, 462 U.S. 696 (1983), that 'the particular course of investigation that the agents intended to pursue here -- exposure of respondent's luggage, which was located in a public place, to a trained canine -- did not constitute a 'search' within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.' Id. at 707. The rationale for the holding is that 'the sniff discloses only the presence or absence of narcotics, a contraband item.' Id. In Place, the United States Supreme Court was not addressing the use of law enforcement investigatory techniques at a house as in Kyllo, but rather only whether a dog sniff of luggage in a public airport constituted a search under the Fourth Amendment. The function of 'place' in Fourth Amendment jurisprudence was instrumental in the decision in Place. "'Place' is no less key in the case at bar. We are of the view that luggage located in a public airport is quite different from a house, not only in physical attributes, but also in the historical protection granted by law. In United States v. Thomas, 757 F.2d 1359, 1366 (2d Cir. 1985), the Second Circuit compared the dog sniff of luggage in Place with that of an apartment, and concluded that "a practice that is not intrusive in a public airport may be intrusive when employed at a person's home.' The rationale for this conclusion is that "the defendant had a legitimate expectation that the contents of his closed apartment would remain private, that they could not be 'sensed' from outside his door. Use of the trained dog impermissibly intruded on that legitimate expectation.' Id. 1367. "This logic is no different than that expressed in Kyllo, one of the recent pronouncements by the United States Supreme Court on law enforcement searches of houses. The use of the dog, like the use of a thermal imager, allowed law enforcement to use sense-enhancing technology to intrude into the constitutionally-protected area of Rabb's house, which is reasonably considered a search violative of Rabb's expectation of privacy in his retreat. Likewise, it is of no importance that a dog sniff provides limited information regarding only the presence or absence of contraband, because as in Kyllo, the quality or quantity of information obtained through the search is not the feared injury. Rather, it is the fact that law enforcement endeavored to obtain the information from inside the house at all, or in this case, the fact that a dog's sense of smell crossed the 'firm line' of Fourth Amendment protection at the door of Rabb's house. Because the smell of marijuana had its source in Rabb's house, it was an 'intimate detail' of that house, no less so than the ambient temperature inside Kyllo's house. Until the United States Supreme Court indicates otherwise, therefore, we are bound to conclude that the use of a dog sniff to detect contraband inside a house does not pass constitutional muster. The dog sniff at the house in this case constitutes an illegal search." An earlier case in State v. Rabb is from 4th DCA 09/14/05 at http://www.4dca.org/Sept%202005/09-14-05/4D02-5139.pdf

Illinois v. Caballes, 03-923 Supreme Court to Rule on Drug Dogs in Traffic Stops WASHINGTON, April 5 2004. Audio recordings of the oral arguments in Caballes can be heard or downloaded at http://www.oyez.org/oyez/resource/case/1751/ The reading of the opinion can also be heard at that url. When Roy Caballes was pulled over by an Illinois state trooper for speeding on a rainy night in 1998, the incident did not seem to be grist for a Supreme Court case. But as Mr. Caballes's car was sitting beside Interstate 80 in La Salle County, another trooper arrived with a police dog. The dog sniffed around it for the presence of drugs, and marijuana was found in the trunk. Mr. Caballes was given only a warning for speeding (he had been clocked at 71 miles an hour in a 65 m.p.h. zone), but he was in big trouble because of the marijuana, since he had prior drug-related arrests. The 1998 arrest resulted in a conviction on marijuana-trafficking charges, a sentence of 12 years in prison and a fine of more than $250,000. Mr. Caballes appealed, contending that the trial court should have suppressed the evidence of the drugs found in the trunk and thrown out the arrest because the police had improperly widened the bounds of an ordinary traffic stop. An Illinois appeals court rejected Mr. Caballes's argument, finding that the sniff by the dog was justified. But the Illinois Supreme Court sided with the defendant, ruling 4 to 3 that the sniff was conducted without "specific and articulable facts" and throwing out the conviction. The Illinois justices said the fact that the aroma of air-freshener was obvious in the defendant's car and his apparent nervousness even after being told he was being given only a warning for speeding could account for "nothing more than a vague hunch" on the part of the troopers, not a sufficient basis to let the dog sniff. (One fact not explained in any of the legal paperwork is why Mr. Caballes was pulled over in the first place, since he was going a mere 6 m.p.h. over the limit.) In any event, the Illinois attorney general, Lisa Madigan, has appealed the Illinois Supreme Court ruling. So within the next several months, the United States Supreme Court will rule on Mr. Caballes's fate, and perhaps clarify when a sniff is a search, and when it is just a sniff. It is yet another in a series of cases weighing police officers' power to look for wrongdoing against the Constitution's Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures.

In a Michigan case from more than a decade ago, the justices upheld sobriety checkpoints as a means of protecting public safety by getting drunken drivers off the road. The Supreme Court has also ruled that a sniff by a drug-detecting dog, which is commonly used at airports, is so minimally intrusive as not to constitute a search.

But in a 2000 case from Indianapolis, the justices ruled that roadblocks aimed at discovering drugs violate the Fourth Amendment. The majority held that "the generalized and ever-present possibility that interrogation and inspection may reveal that any given motorist has committed some crime" was insufficient justification for wholesale stops.

US v. Robinson 6th Circuit (argued Oct 2003) Whether an "ancient" sniff trained dog is sufficient for probable cause that marijuana is present at the time of the sniff is an issue. A significant issue remains as to whether the dog is trained to quantitative amounts or to historic presence, i.e. that marijuana has been present sometime in the past but may not be there at the time of the sniff.

Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27 (2001), Docket Number: 99-8508 audio is at http://www.oyez.org/oyez/resource/case/1304/ A Department of the Interior agent, suspicious that Danny Kyllo was growing marijuana, used a thermal-imaging device to scan his triplex. The imaging was to be used to determine if the amount of heat emanating from the home was consistent with the high-intensity lamps typically used for indoor marijuana growth. Subsequently, the imaging revealed that relatively hot areas existed, compared to the rest of the home. Based on informants, utility bills, and the thermal imaging, a federal magistrate judge issued a warrant to search Kyllo's home. The search unveiled growing marijuana. After Kyllo was indicted on a federal drug charge, he unsuccessfully moved to suppress the evidence seized from his home and then entered a conditional guilty plea. Ultimately affirming, the Court of Appeals held that Kyllo had shown no subjective expectation of privacy because he had made no attempt to conceal the heat escaping from his home, and even if he had, there was no objectively reasonable expectation of privacy because the imager "did not expose any intimate details of Kyllo's life," only "amorphous 'hot spots' on the roof and exterior wall." Question Presented: Does the use of a thermal-imaging device to detect relative amounts of heat emanating from a private home constitute an unconstitutional search in violation of the Fourth Amendment? Conclusion: Yes. In a 5-4 opinion delivered by Justice Antonin Scalia, the Court held that "[w]here, as here, the Government uses a device that is not in general public use, to explore details of the home that would previously have been unknowable without physical intrusion, the surveillance is a 'search' and is presumptively unreasonable without a warrant." In dissent, Justice John Paul Stevens argued that the "observations were made with a fairly primitive thermal imager that gathered data exposed on the outside of [Kyllo's] home but did not invade any constitutionally protected interest in privacy," and were, thus, "information in the public domain."

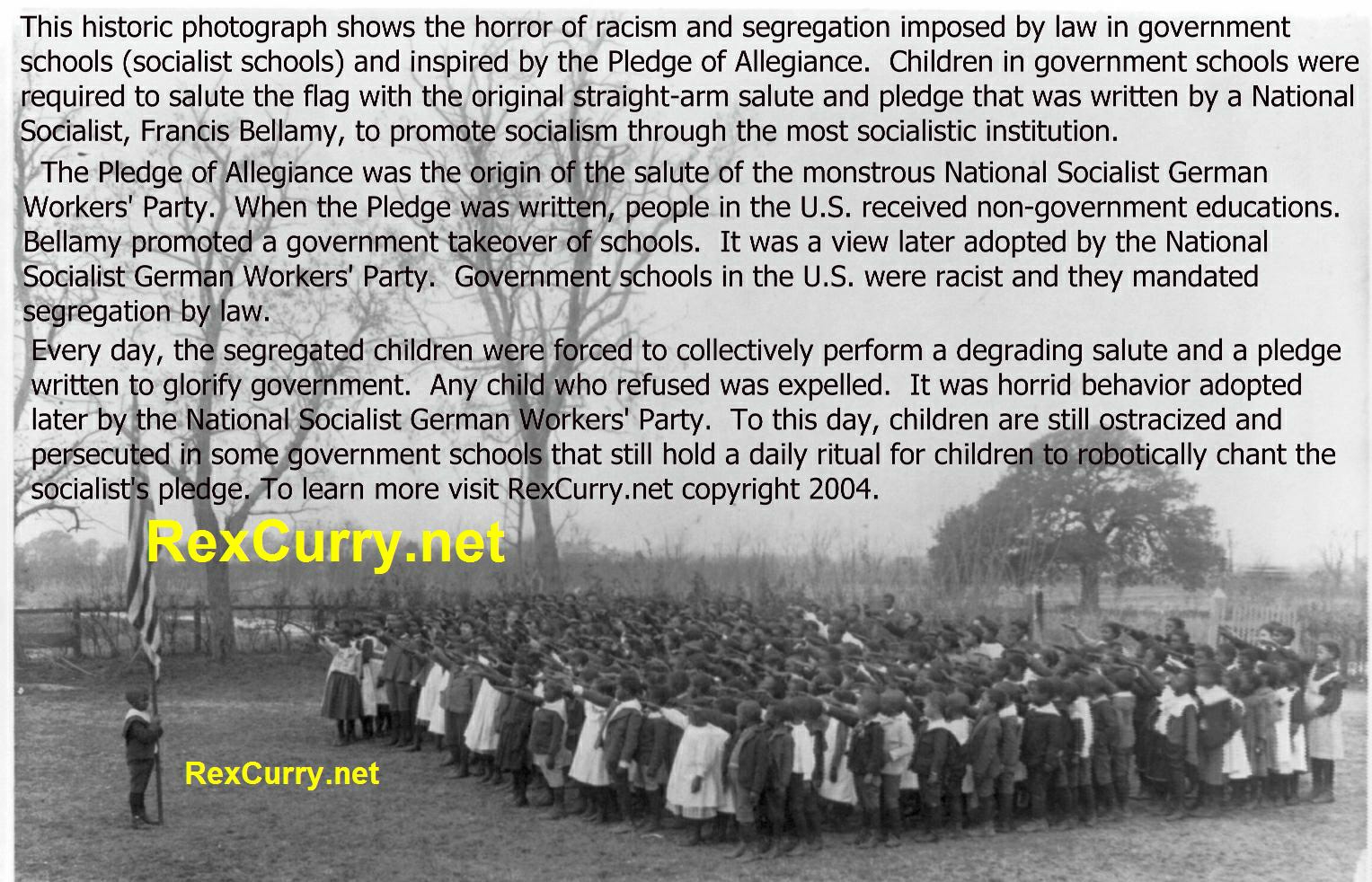

Dr. Rex Curry exposed the myths about drug dogs, sniffer dogs, police dogs, drug detection dogs, narco dogs, bomb dogs, explosives dogs, narcotics dogs, and police searches and seizures http://rexcurry.net/drugdogsmain.html

Court Cases

This case is a very important case yet many other police dog sites choose not to reveal it. The case went to the US Supreme Court and the court refused to hear it. It is a very important case that handlers should consider seriously. I have not found it posted on any other K9 website.

- Citrus drug dog's missing records throw a wrench into two cases these cases are the result of Matheson.

- Another link about the Matheson case.

STATE OF TENNESSEE v. KEVON FLY After Officer Carter wrote the defendant citations for failure to possess proof of insurance and a driver’s license, he asked the defendant for permission to search his vehicle. The defendant denied the permission. The officer asked the defendant to step out of his car and informed him that the officer’s dog, Rico. Tennessee Court of Appeals held that after the business of the traffic stop was complete searching the exterior of the vehicle without consent or probable cause was an illegal search.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. GREG RENE ESPARZA Case No. CR-07-14-S-BLW, MEMORANDUM DECISION AND ORDER

This is a case involving the use of an explosive detector dog as if it were a drug detector dog. The court held that using an explosive dog as a sniff was a search that violated 4th amendment rights.

United States vs. Patterson, 65 F, 3d 68 Wisconsin 1995 Of all the cases out there based on what I consider poorly trained dog teams this one takes the cake. In my opinion if a dog cannot work through this really simplistic situtation it has no business on the street, and the person responsible for training and maintaing this dog is not a knowledgeable trainer.

Chief District Judge Joseph F. Bataillon recently dismissed eveidence in a drug case Douglas County Deputy Sheriff Douglas Wintle, and his drug detector dog. The judge in this case appeared to understand that if the dog is reliable there is no need to spent 33 minutes as this handler did collecting information before running the dog. Also, the judge seemed to understand that claims or residual was not the same as actually finding drugs. The judge also understood, it is unnecessary for a well trained dog to be prompted by the handler or someone acting like they were hidding something to get the dog to search, and that once the dog has completed one pass around the vehicle without responding that was it. Also, repeatly taking the dog back to an area and then saying the dog responded to that area is not acceptable to this judge. Mabe this judge has opened the door for those trainer who do not know how to teach a dog to begin searching calmly and intently on command, and to respond without handler imput, to pass on out. Hopefully so then those interested in really taking drugs off the street using the dogs will be left. Then we can have real drug dogs and not probable cause dogs.

State of Utah vs. Rafael Alegria

In this case the judge ruled the dog reliable. But it goes to show what can happen by not trusting your dog. Stop asking all those questions they do nothing to help your dog and can in fact as in this case have an adverse effect. Trust your dog. If you don't trust your dog enought to run it without all those questions get another dog, or another trainer.

This team was trained and certified by Alderhorst International. The Sergeant and head trainer for Arizona DPS testified as an expert supporting the report submitted by David Reaver owner of Alderhorst International. The court found the dog was not reliable and the certification process invalid. Those using dogs trained and certified by Alderhorst International should review this case and compare it with their recordkeeping and certification procedures. Having reviewed at least 4 different dogs trained and certified all teams performed very similar.

This was the second time this case had

been before the courts. In the first case Wendell Nope was standing by to

testify, but the Judge ruled that probable cause existed without the dog.

Federal Judge Campbell stopped the calling of Wendell Nope to the stand. Sgt.

Nope was going to support a non-certified dog as being reliable. Judge Campbell

make it clear they prosecution did not want her to rule on the reliability

of the dog. She said that Mr. Nicely’s testimony

was too convincing. The Judge in the 2nd hearing heard the testimony

of the handler and Sgt. Wendell Nope as well as Mr. Nicely and concluded “the court credits Mr.

Nicely’s testimony over that of Officer

Anderson and/or Sgt. Nope, the court finds that Defendant has satisfied his

burden of demonstrating that Oso was unqualified

to serve as a narcotics detection dog at the time he was deployed in this

case.”

An Eleventh Circuit case struck down mandatory metal detectors for protest attendees. BOURGEOIS v. PETERS at http://www.ca11.uscourts.gov/opinions/ops/200216886.pdf

It struck down a city police policy requiring everyone attending a November 2002 protest against the "School of the Americas" to pass through a metal detector violated the Fourth and First Amendments.

The court's opinion is particularly notable for its rebuke of the city's effort to justify use of the metal detector based on 9/11:

The City's brief begins with the bold declaration that "[l]ocal governments need an opinion that, without question, allows non-discriminatory, low-level magnetometer searches at large gatherings." Appellees' Brief at 13. Citing nothing more than a single case from 1980, the City contends that "[p]ost September 11, 2001, this Court can determine [that] the preventive measure of a magnetometer at large gatherings is constitutional as a matter of law." Id. (citing Donovan v. Dewey, 452 U.S. 594, 606 (1980)).

This argument is troubling. While the threat of terrorism is omnipresent, we cannot use it as the basis for restricting the scope of the Fourth Amendment's protections in any large gathering of people. In the absence of some reason to believe that international terrorists would target or infiltrate this protest, there is no basis for using September 11 as an excuse for searching the protestors.

Even putting aside the City's ill-advised and groundless reference to September 11, its demand for the unbridled power to perform "magnetometer searches at [all] large gatherings" is untenable. The text of the Fourth Amendment contains no exception for large gatherings of people. . . .

A great case, it is also perplexing for another reason: It cites Wikipedia, an anonymous bulletin board (touted as an online collaborative encyclopedia), for information on the Department of Homeland Security Advisory System. It might be one of only two times that a court has cited Wikipedia, the other being Bryant v. Oakpointe Villa Nursing Ctr., 471 Mich. 411 (2004), a Michigan Supreme Court case, which cites Wikipedia for information on positional asphyxia.

Police officers said "If you don't consent to search, we'll kill this dog!" http://rexcurry.net/dog4.jpg

Katz v. United States 389 U.S. 347 (1967) Decided December 18, 1967: Acting on a suspicion that Katz was transmitting gambling information over the phone to clients in other states, Federal agents attached an eavesdropping device to the outside of a public phone booth used by Katz. Based on recordings of his end of the conversations, Katz was convicted under an eight-count indictment for the illegal transmission of wagering information from Los Angeles to Boston and Miami. On appeal, Katz challanged his conviction arguing that the recordings could not be used as evidence against him. The Court of Appeals rejected this point, noting the absence of a physical intrusion into the phone booth itself. The Court granted certiorari. Question Presented: Does the Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable searches and seizures require the police to obtain a search warrant in order to wiretap a public pay phone? Conclusion: Yes. The Court ruled that Katz was entitled to Fourth Amendment protection for his conversations and that a physical intrusion into the area he occupied was unnecessary to bring the Amendment into play. "The Fourth Amendment protects people, not places," wrote Justice Potter Stewart for the Court. A concurring opinion by John Marshall Harlan introduced the idea of a 'reasonable' expectation of Fourth Amendment protection. The government gambles away freedom by chasing Katz. Putting a leash on politicians is like herding cats.

The Sheriff said "I'll kill myself if you don't waive your rights!" http://rexcurry.net/police-state-sheriff-blazing-saddles.jpg