The NACDL's Amicus Brief argument is below.

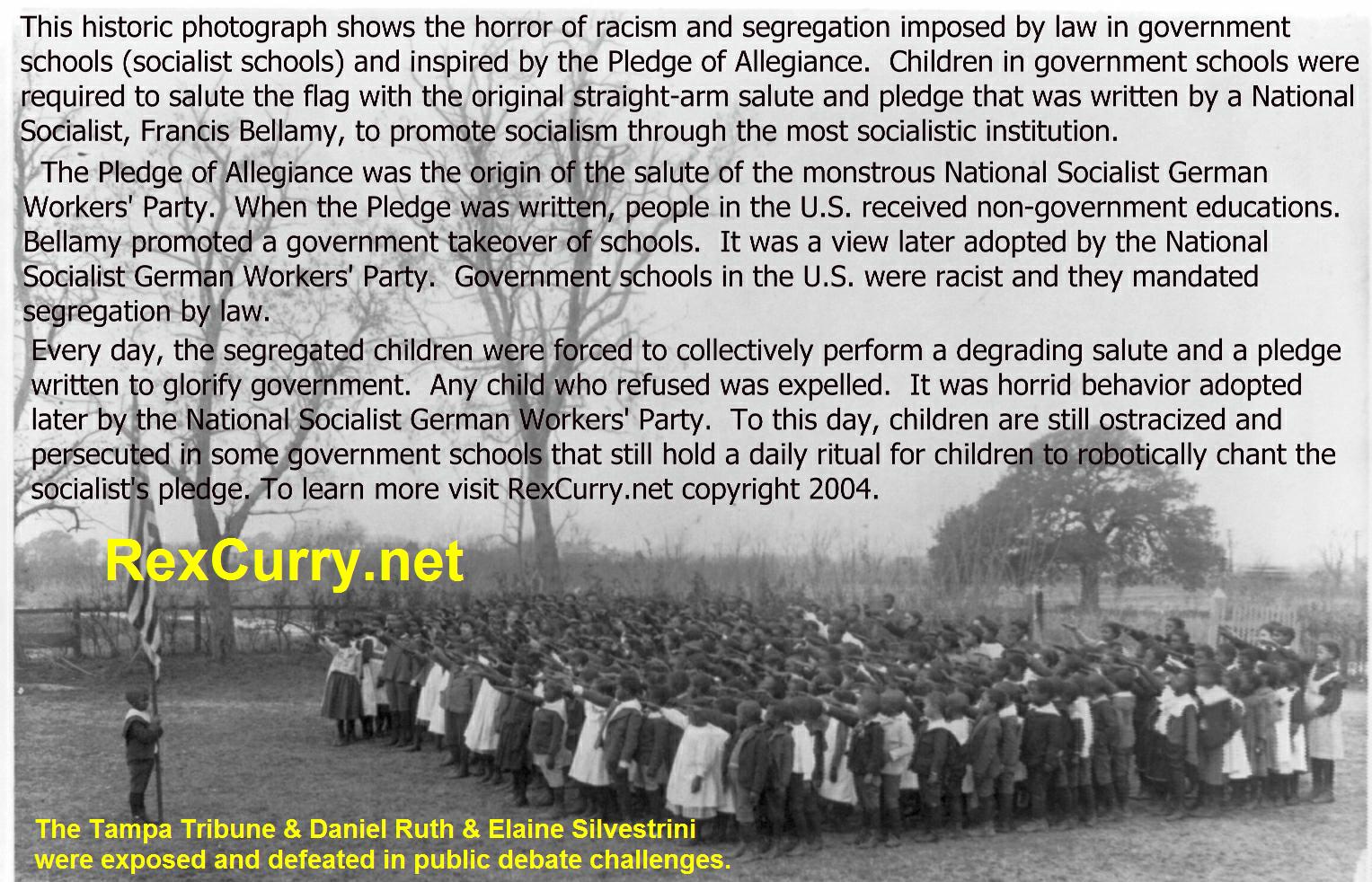

See more eye-popping, jaw-dropping photographs at http://rexcurry.net/pledge2.html

Read more amazing articles about every aspect of the totalitarian pledge at http://rexcurry.net/pledge1.html

|

WONSCHIK v. U.S. The NACDL's Amicus Brief argument is below. See more eye-popping, jaw-dropping photographs at http://rexcurry.net/pledge2.html Read more amazing articles about every aspect of the totalitarian pledge at http://rexcurry.net/pledge1.html |

| Support the "STOP THE PLEDGE" Campaign and support historical and educational research about the Pledge, its author and his ilk. |

| It is ironic to note that West

Virginia had banned the American salute in 1942 even though it continued to

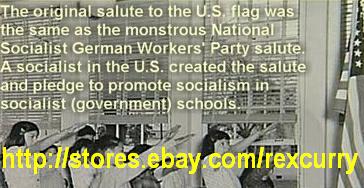

compel the robotic chanting daily. http://rexcurry.net/pledgenacdl.html The following excerpt is from an article in the New York Times - West Virginia Banishes 'Nazi' Salute in Schools By The United Press. on February 2, 1942, Monday CHARLESTON, W. Va., Feb. 1 -- West Virginia has decided to have its school children salute the American flag the way grown-ups do because the present classroom salute is "too much like Hitler's." The change was agreed upon by the State Board of Education after a conference with patriotic and educational organizations which had reported complaints from parents. For a photograph of the early Pledge of Allegiance see http://rexcurry.net/pledge-allegiance-pledge-allegiance2.jpg |

| Pledge of Allegiance controversy

over America's early Nazi salute. http://rexcurry.net/pledgenacdl.html Excerpts from New York Times March 9, 1937, Tuesday - SCHOOLS HERE TRY 'NAZI-TYPE' SALUTE; Row Raised Over New Pledge to Flag With Extended Arm--Principals Assail Idea A new type of flag salute, recommended by the State Department of Education and submitted to the principals through a circular issued by Harold G. Campbell, Superintendent of Schools, has brought confusion and uncertainty as to the proper method of pledging allegiance to the American flag, it was learned yesterday. In the traditional military salute the hand is raised to the head, at the proper time raised straight and then whipped briskly to the side. THE OLD AND NEW SCHOOLBOY SALUTE TO THE FLAG Students of Bryant High School in Queens demonstrating the change of posture as the Pledge of Allegiance is ... "We still have the traditional salute in the New York City schools," he said. ... "I can see no cause of alarm-this salute: does not try to copy Hitler's ... For a photograph of the early Pledge of Allegiance see http://rexcurry.net/pledge-allegiance-pledge-allegiance2.jpg **************** Army Salute for Children October 3, 1941, Friday New York Times ... use the regulation Army salute in the daily pledge of allegiance to the flag. ... the arm-extended salute because of its similarity to the Nazi greeting. ********************** The Syracuse Herald, Thursday, March 25, 1937 Rural School Choice OF Flag Salutes .. military fashion as the first words of pledge of allegiance are Although the ... salute is nothing either Nazi or Fascist about the suggested Mr Shingle ... http://rexcurry.net/pledge-of-allegiance1942fresno.pdf http://rexcurry.net/pledge-of-allegiance1941iowa-military.pdf http://rexcurry.net/pledge-of-allegiance1941jehovah-catholic.pdf http://rexcurry.net/pledge-of-allegiance1942lowell-mass.pdf http://rexcurry.net/pledge-of-allegiance1937syracuse-herald.pdf http://rexcurry.net/pledge-of-allegiance1937new-york.pdf |

| In this case, the selection process was impermissibly

tainted by the trial judge's request that all potential jurors stand and

recite the Pledge of Allegiance prior to jury selection. |

|